From Epistory to Nanotale

When we released our first game Epistory, we wanted to do something different from what you could find on the market. One of the ideas was to create a typing game. We didn’t know if there was an audience for it, as many people associated typing to educational games such as Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing or Mario Teaches Typing. When we tried some typing games and discovered such alien games as Typing of The Dead, we found out that typing could be fun if well executed.

We created a prototype of Epistory that is still playable here but keep in mind that it’s really barebone, and no artist was involved (it’s made with the Construct 2 engine). After that point, development restarted from scratch, with a different engine (Unity 3D), but with all the experience we gathered from the prototype. We put all our efforts into what was intended to be an adventure game with a typing mechanic. After a year of development, we released the game on Steam in March 2016, and the game has an overwhelmingly positive rating now.

To be honest, creating Nanotale was not a part of our plan. But, we received a lot of requests from the community asking us to create a new typing game. They asked for an Epistory 2. We thought a bit about it and asked them with a survey of how they would like their new typing game.

The answers were quite interesting and diversified but they all agreed on one thing: They wanted it to be Epistory but better.

A New Look for a New Game

Finding the right art style for Nanotale was probably the biggest challenge in that production. Our community loved the art style of Epistory so much that they specifically asked us not to change it. That art style is somehow linked to the story of Epistory, we decided to do the same for Nanotale, and that the new story required its own style. We wanted Nanotale to be different from its predecessor, with a new story, new gameplay elements, new characters, and a brand new art style. All while keeping the elements that our community loved so much: something unique and poetic.

Epistory - Typing Chronicles (screenshot from the Shattered Isles)

Nanotale - Typing Chronicles (screenshot from the Ancestral Forest)

A Long Road Searching for The One

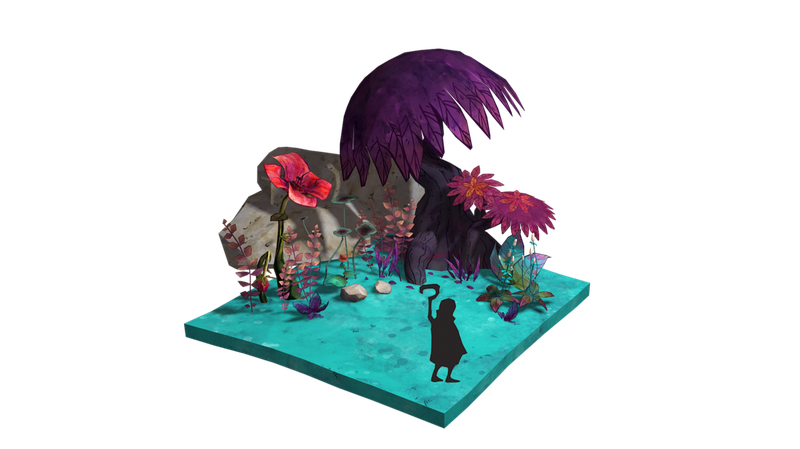

A never-ending journey brought us from the first art iteration to the final look of Nanotale, starting with these two concept arts.

Back then, we were searching for a poetic mood in a fantastic world and didn’t know that they would inspire us for the second biome of the game. What really caught our interest at that point was the use of contrast between areas of light and darkness; a game made of chiaroscuro.

Based on these concepts, we took the first screenshots of the game and shared a few online. But they felt too classic. That was not what we wanted: not poetic enough, not recognizable enough. They could have been from any other game out there.

So we went back to the drawing board, trying to find the right tone, the perfect light. We wanted to give Nanotale its own visual identity.

When our 2D artist created those, we knew that we had found the right color scheme for our game: something pastel and dark, moody and bright at the same time.

After that, the challenge was to convey that ambiance to the art style we would have in the game. How to inject Epistory’s soul in that new art style while being fresh and new? What made Epistory unique for the players? Was it the papercraft/origami? Was it the paintings from the meta-story? Having a look back at our first game gave us the idea to make Nanotale a watercolor painting.

The watercolor painting was a great idea for the still images but Nanotale is a 3D game. To make watercolor in 3D, we found a 3D model on Sketchfab that was amazing and that inspired us the technique.

A 3D Watercolor Art Style

For modelization, we keep in mind that we want something low poly, but we don’t hesitate to put more polygons where we need them, like on the characters or the ground. For the rocks and plants, we keep a very low poly count, and we play with the ambient occlusion to create nice volumes.

The textures are also very important in our process: we work with watercolor brushes to put some colors. Then we refine the details with strokes to better understand the shape and add some complexity. We never use a normal map or specular because we want to keep full control of the final look of every asset. Depending on the asset, we sometimes bake the low poly mesh on itself and get some information like the ambient occlusion that we use as a base for the texture.

A Magical Decoration Process

In our decoration process, we use home-made Houdini digital assets (HDA) to quickly generate rock walls, forest patches or ground platforms. These HDA take time to prepare but the procedural workflow allows us to save time on building environments, so we can spend more time on decoration details to make every screen unique and mastered.

Besides the natural environment, we also worked on the city of the second biome. Once the concept is done, the first draft we do in 3D is for the volume blocking. The complexity of the city makes it harder to edit than any other environment. Starting with a solid base is important as we are working with a lot of small pieces to build the houses.

Concept art of the city from the Sunken Caves

First 3D draft of the city

In Nanotale, we are not working with a high-poly model or normal map in the material, so it's important to create a small scene quickly with our low poly assets to see how it looks like before starting the texturing.

We first validate the modelization, then work on the texture where we add more details. The mix of tileable and trim textures allows us to avoid having too many specific and individual textures. The lighting is done, while we are still tweaking the texture to make sure we have the perfect result we everything comes together.

The finished city in the game

The in-game city used to create our Steam banner

Imparting Life with Houdini

We want the animations to be short and with a cartoon feeling, so they are readable with the camera view we have in-game. That cartoon feeling requires flexibility for some bouncy animations that impact the creation of the rig.

After doing the rigging part and setting the list of animations we want per character, we first do the animation that best conveys the character’s intention. That reference animation defines the expected mood of the character.

In our animation process, we define the main poses of the animation. Then, we play with the timeline to adjust the timing. This has to be done right because after this step it's more difficult to re-adjust the timing.

Our animations have three phases:

- Anticipation

- Action

- Return to the main Pose

To have a quick and responding animation we have to cut the anticipation and try to put it at the end. The best impact is achieved with a quick start and a long reception with some bounciness.

When we have good timing, we start editing the curve to fluidify animation and do some adjustments.

The main goal is not to have a pure polished animation but to have all the animations set in rough mode. It’s crucial to test quickly the entire flow of the animation tree in Unity, to see if it's already readable, looks nice, and is understandable, before starting polishing and adding details.

When all the animations are working, it’s important to take a break and work on other things, and come back later to rework on them with a clear mind.

The polished animation after a refreshing break

A Peculiar Game Mechanic

Because the game uses a keyboard to control everything (besides basic movement), typing mechanics need to be convenient to use and not too restricting. It is frustrating to feel forced to use a keyboard for something that could be more easily controlled with a mouse or a gamepad (which is why you still move with WASD). So we try to keep all the typing related to the action performed: combining magic words to cast a spell, typing keywords to select a dialog topic or to write lore in your notebook. Occasionally, for controls that are not used all the time, we allow ourselves to use fun controls based on keyboard patterns rather than actual words.

When we ask players to type more words and faster, putting them under pressure in a battle, it gives the satisfying feeling of defeating something that seemed really hard, but that is made easier because of your muscle memory (sometimes you lose, of course, but my point is that most players underestimate their typing skills). Unfortunately, we cannot make the typing controls deeper than that. When you challenge typing on something else than speed or accuracy, it becomes really tedious and frustrating. (We tried typing slowly, typing in rhythm, typing non-English words, typing symbols…). Because the typing mechanics have to stay simple, the game design is composed of simple typing-based gameplays, connected together in a systematic way. For example, typing a spell is simple, but the different combinable keywords allow for multiple approaches to each situation.

The Real Challenge is Coming

Nanotale is out in early access since the 23rd of October 2019, and there are a lot of things that need to be done before releasing the final game. We are happy about what we released so far even if multiple aspects of the game required a lot of iterations, and we hope that the community will enjoy the game. I think that dealing with the early access and the development will be the biggest challenge so far.

Thank you for reading.