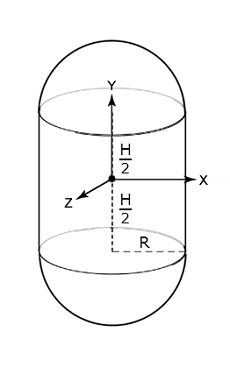

Concept

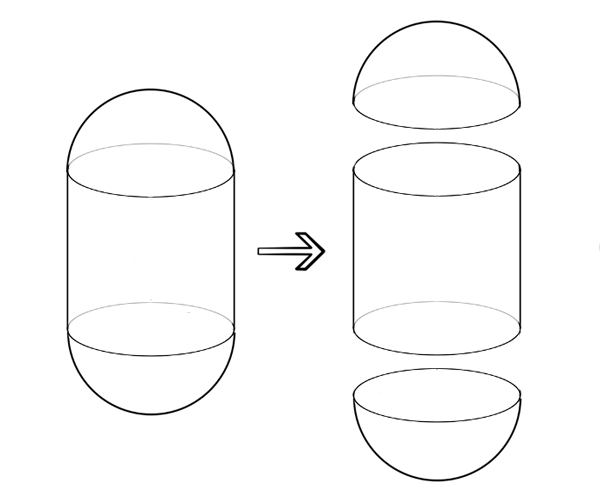

Firstly, what is meant by saying capsule? Well, simply put, it is a cylinder that (instead of flat ends) has hemispherical ends. By cylinder I mean a circular one (not elliptical). Hemispheres have the same radius. It should also be mentioned that the given body is solid (not hollow). Where H is height of the cylinder part and R is radius of the hemisphere caps. This is the coordinate system that has its origin in the center of the mass of the capsule and whose axes are the axes which we will be calculating moments of inertia for. Figure 2. Capsule decomposition.

Figure 2. Capsule decomposition.

(eq. 1)

V represents the three dimensional region of integration and dm is an infinitesimal amount of mass at some point in our capsule. The integrand is simply squared distance from the axis.(eq. 2)

Note that in eq. 2 products of inertia are equal to zero. There exists a theorem that says that it is possible to find three (mutually perpendicular) axes for every body so the tensor produced from those axes has zero products of inertia. Those axes are called the principal axes. Furthermore, for bodies with constant density an axis of rotational symmetry is a principal axis. We have three perpendicular axes of rotational symmetry for our capsule. First one is the y axis of continuous rotational symmetry and then there are x and z axes of discrete rotational symmetry. I will not go into detail about what axes of rotational symmetry are, but I recommend to go and check it out.(eq. 3)

Since we will integrate over space eq. 3 will be used. If density is required to be some other constant than 1, the end result can simply be multiplied by that constant.Cylinder

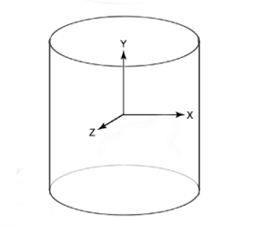

Before we dive into integration here is the Cartesian coordiante system we will be using for cylinder: Figure 3. Cylinder and its position relative to coordinate system.

Figure 3. Cylinder and its position relative to coordinate system.

(eq. 4)

First we add up (integrate) over 2*pi*r interval to get the moment of inertia of a circular curve around the y axis. After that we integrate that curve over the interval R to get the moment of inertia of a disc surface perpendicular to the y axis. Lastly those discs are added up across [-H/2, H/2] interval to get the moment of inertia of a whole cylinder. The integral for the mass of a cylinder is very similar and follows the same intuition. It is given by:(eq. 5)

Now, slightly more complicated integrals are the ones for moments of inertia around x and z axis. Those are equal, so only one calculation is needed. Note that we are back in Cartesian coordinates for this one and the integral is set up like we are calculating Ixx.(eq. 6)

This is it for the cylinder as I will not go into detail about intuition for this integral since there is more work to be done for hemisphere caps.Hemisphere caps

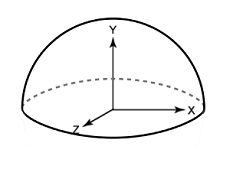

The following is how the hemisphere is defined relative to Cartesian coordinate system for the purpose of integration: Figure 4. Hemisphere and its position relative to coordinate system.

Figure 4. Hemisphere and its position relative to coordinate system.

(eq. 7)

We are in the cylindrical coordinate system and the intuition is similar to eq. 4. The only difference is that now the radius of a disc we need to integrate is a variable of the y position of a disc (sqrt(R^2 - y^2)). Then we just integrate those discs from 0 to R and we end up with the whole hemisphere region. As for the cylinder, the integral for the mass of a hemisphere follows the same intuition and is given by:(eq. 8)

Now, when we try to calculate the moments of inertia around x and z axis (which are equal), things get tricky. Note that integral is set up like we are calculating Ixx:(eq. 9)

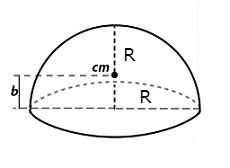

Figure 5. Center of mass of a hemisphere.

Figure 5. Center of mass of a hemisphere.

(eq. 10)

(eq. 11)

Where Icm is moment of inertia of an axis that goes through the center of mass and m is hemisphere mass from eq. 8. Now it's finally possible to calculate Ixx and Izz for our hemisphere caps. We can now apply Steiner's rule to translate the axes from the center of mass of a hemisphere to the center of mass of the whole body (capsule):(eq. 12)

Moments of inertia for the hemisphere cap on the bottom of the capsule do not differ to those here.The tensor

(eq. 13)

Equations in eq. 13 give us separated masses of cylinder and hemisphere as well as the mass of the whole body. Notice how mass of the hemisphere (mhs) is multiplied by two. This is, of course, because there are two hemispheres on both ends of the capsule. Also, note our previous assumption in which density is equal to one unit of measurement, which is why the mass is equal to volume. If needed mcy and mhs can simply be multiplied by some constant density and the results will be accurate. The given code is written in such way. The full tensor uses this values and is given by:(eq. 14)

Although previously shown formulas for moments of inertia are not given by mcy and mhs, by substituting those values equality can be easily shown. The parts that represent moments of inertia of a hemisphere are multiplied by two, because we have two of them.Code

The following code implementation is given in C-like language and is fairly optimized.

#define PI 3.141592654f

#define PI_TIMES2 6.283185307f

const float oneDiv3 = (float)(1.0 / 3.0);

const float oneDiv8 = (float)(1.0 / 8.0);

const float oneDiv12 = (float)(1.0 / 12.0);

void ComputeRigidBodyProperties_Capsule(float capsuleHeight, float capsuleRadius, float density,

float &mass, float3 ¢erOfMass, float3x3 &inertia)

{

float cM; // cylinder mass

float hsM; // mass of hemispheres

float rSq = capsuleRadius*capsuleRadius;

cM = PI*capsuleHeight*rSq*density;

hsM = PI_TIMES2*oneDiv3*rSq*capsuleRadius*density;

// from cylinder

inertia._22 = rSq*cM*0.5f;

inertia._11 = inertia._33 = inertia._22*0.5f + cM*capsuleHeight*capsuleHeight*oneDiv12;

// from hemispheres

float temp0 = hsM*2.0f*rSq / 5.0f;

inertia._22 += temp0 * 2.0f;

float temp1 = capsuleHeight*0.5f;

float temp2 = temp0 + hsM*(temp1*temp1 + 3.0f*oneDiv8*capsuleHeight*capsuleRadius);

inertia._11 += temp2 * 2.0f;

inertia._33 += temp2 * 2.0f;

inertia._12 = inertia._13 = inertia._21 = inertia._23 = inertia._31 = inertia._32 = 0.0f;

mass = cM + hsM * 2.0f;

centerOfMass = {0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f};

}

It would seem that centerOfMass is useless, but I have left it here because it is important part of rigid body properties and often a requirement for physics engines.

Hi Bojan,

Nice article! I have a few questions that you can probably clear up for me.

First, it seems that the 'float3 &cm' argument is not being used for anything, and is just being hardcoded to 0 at the end of the method. Is this intentional? If so, is there a point to actually having it?

Second, am I correct in understanding that for capsules of varying masses, we would simply multiply a value representing the density by the result stored in 'float &mass'? Or is there a bit more to it than that? In other words, using the above code, how do I distinguish a representation of an object with mass 100 kg versus an object with mass 20 kg?

Thanks,

WFP