Previous Articles Some systems need to manipulate objects whose exact nature are not known. For example, a particle system has to manipulate particles that sometimes have mass, sometimes a full 3D rotation, sometimes only 2D rotation, etc. (A

good particle system anyway, a bad particle system could use the same struct for all particles in all effects. And the struct could have some fields called

custom_1,

custom_2 used for different purposes in different effects. And it would be both inefficient, inflexible and messy.) Another example is a networking system tasked with synchronizing game objects between clients and servers. A very general such system might want to treat the objects as open JSON-like structs, with arbitrary fields and values:

{ "score" : 100, "name": "Player 1" } We want to be able to handle such "general" or "open" objects in C++ in a nice way. Since we care about structure we don't want the system to be strongly coupled to the layout of the objects it manages. And since we are performance junkies, we would like to do it in a way that doesn't completely kill performance. i.e., we

don't want everything to inherit from a base class Object and define our JSON-like objects as:

typedef std::map OpenStruct; Generally speaking, there are three possible levels of flexibility with which we can work with objects and types in a programming language:

1. Exact typing - Only ducks are ducks

We require the object to

be of a specific type. This is the typing method used in C and for classes without inheritance in C++.

2. Interface typing - If it says it's a duck

We require the object to inherit from and implement a specific interface type. This is the typing method used by default in Java and C# and in C++ when inheritance and virtual methods are used. It is more flexible that the exact approach, but still introduces a coupling, because it forces the objects we manage to inherit a type defined by us. Side rant: My general opinion is that while inheriting

interfaces (abstract classes) is a valid and useful design tool, inheriting

implementations is usually little more than a glorified "hack", a way of patching parent classes by inserting custom code here and there. You almost always get a cleaner design when you build your objects with composition instead of with implementation inheritance.

3. Duck typing - If it quacks like a duck

We don't care about the type of the object at all, as long as it has the fields and methods that we need. An example:

def integrate_position(o, dt): o.position = o.position + o.velocity * dt This method integrates the position of the object

o. It doesn't care what the type of

o is, as long as it has a "position" field and a "velocity" field. Duck typing is the default in many "scripting" languages such as Ruby, Python, Lua and JavaScript. The reflection interface of Java and C# can also be used for duck typing, but unfortunately the code tends to become far less elegant than in the scripting languages:

o.GetType().GetProperty(???????Position???????).SetValue(o, o.GetType(). GetProperty(???????Position???????).GetValue(o, null) + o.GetType(). GetProperty(???????Velocity???????).GetValue(o, null) * dt, null) What we want is some way of doing "duck typing" in C++. Let's look at inheritance and virtual functions first, since that is the standard way of "generalizing" code in C++. It is true that you could do general objects using the inheritance mechanism. You would create a class structure looking something like:

class Object {...}; class Int : public Object {...}; class Float : public Object{...}; and then use

dynamic_cast or perhaps your own hand-rolled RTTI system to determine an object's class. But there are a number of drawbacks with this approach. It is quite verbose. The virtual inheritance model requires objects to be treated as pointers so they (probably) have to be heap allocated. This makes it tricky to get a good memory layout. And that hurts performance. Also, they are not PODs so we will have to do extra work if we want to move them to a co-processor or save them to disk. So I prefer something much simpler. A generic object is just a type enum followed by the data for the object:

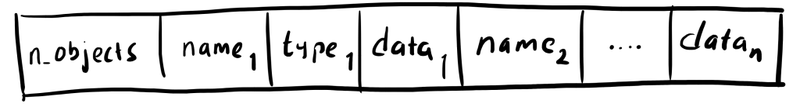

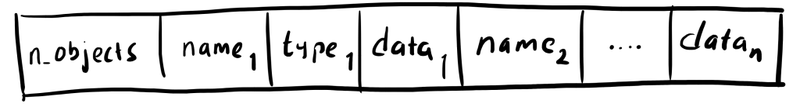

To pass the object you just pass its pointer. To make a copy, you make a copy of the memory block. You can also write it straight to disk and read it back, send it over network or to an SPU for off-core processing. To extract the data from the object you would do something like:

unsigned type = *(unsigned *)o; if (type == FLOAT_TYPE) float f = *(float *)(o + 4); You don't really need that many different object types:

bool,

int,

float,

vector3,

quaternion,

string,

array and

dictionary is usually enough. You can build more complicated types as aggregates of those, just as you do in JSON. For a dictionary object we just store the name/key and type of each object:

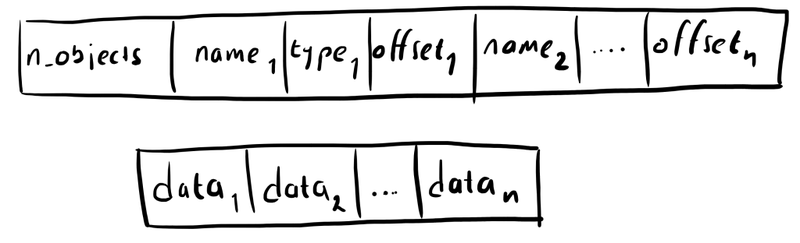

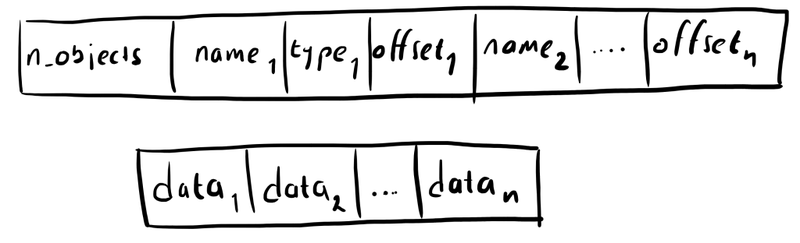

I tend to use a four byte value for the name/key and not care if it is an integer, float or a 32-bit string hash. As long as the data is queried with the same key that it was stored with, the right value will be returned. I only use this method for small structs, so the probability for a hash collision is close to zero and can be handled by "manual resolution". If we have many objects with the same "dictionary type" (i.e. the same set of fields, just different values) it makes sense to break out the definition of the type from the data itself to save space:

Here the

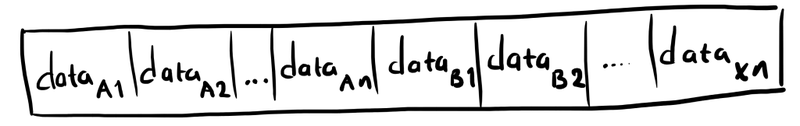

offset field stores the offset of each field in the data block. Now we can efficiently store an array of such data objects with just one copy of the dictionary type information:

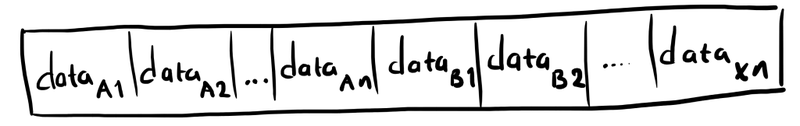

Note that the storage space (and thereby the cache and memory performance) is exactly the same as if we were using an array of regular C structs, even though we are using a completely open free form JSON-like struct. And extracting or changing data just requires a little pointer arithmetic and a cast. This would be a good way of storing particles in a particle system. (Note: This is an array-of-structures approach, you can of course also use duck typing with a sturcture-of-arrays approach. I leave that as an exercise to the reader.) If you are a graphics programmer all of this should look pretty familiar. The "dictionary type description" is very much like a "vertex data description" and the "dictionary data" is awfully similar to "vertex data". This should come as no big surprise. Vertex data is generic flexible data that needs to be processed fast in parallel on in-order processing units. It is not strange that with the same design criterions we end up with a similar solution.

Morale and musings

It is OK to manipulate blocks of raw memory! Pointer arithmetic does not destroy your program! Type casts are not "dirty"! Let your freak flag fly! Data-oriented-design and object-oriented design are not polar opposites. As this example shows a data-oriented design can in a sense be "more object-oriented" than a standard C++ virtual function design, i.e., more similar to how objects work in high level languages such as Ruby and Lua. On the other hand, data-oriented-design and inheritance

are enemies. Because designs based on base class pointers and virtual functions want objects to live individually allocated on the heap. Which means you cannot control the memory layout. Which is what DOD is all about. (Yes, you can probably do clever tricks with custom allocators and patching of vtables for moving or deserializing objects, but why bother, DOD is simpler.) You could also store function pointers in these open structs. Then you would have something very similar to Ruby/Lua objects. This could probably be used for something great. This is left as an exercise to the reader.

Reprinted with permission from The Bitsquid blog.

I like some of your ideas but I can't help but to think that your idea of decoupling is making all functions take void* arguments and making all UDTs char buffers or possibly PODs that are easily castable to continuous memory blocks.

Also calling this solution Duck Typing is a big stretch to say the least. Duck Typing is about behavior not data. It should "walk" and "quack" like a duck and not be "memory access optimized map". std::map<> is not a DT representative nor is presented solution.

Also, it would be nice to see the code that shows how you could replace presented python snipped in C++ with 2 example "types" that share "interface" based on your proposed solution.

Please don't get me wrong. I like the article very much, in fact I try to read everything you write and I am now also thinking how to wrap your "dynamic type" in templates to make a nice interface to underlying buffer. Would kindof be similar to boost::flat_map i suppose in which key-value pairs are stored in a vector (instead of a node-based tree) for the best cache usage.