A revised edition of this article combining all 4 parts is now available hereCan you believe it? Here's part IV! I was looking around the internet and was shocked at how little information they have on this stuff! So I decided to keep on writing these things until I run out of things to talk about. (Well, this broken leg of mine might be a reason I've got so much free time...don't ask. Okay, since you asked, I got it while skating...so now I can't skate for about two months...DOH!) Once again, this series of articles is designed to turn you into a game music composer. If you know absolutely nothing about music, then you don't have to worry, just read parts I, II, and III before reading this part. Now, what we gonna do in this part, John? Well, articles I, II and III turned you into an amateur music composer. Hopefully by now, you've read them and written a few songs. This addition to the series is going to be about how to write better songs. For example, how to write an opening of a song, how to build up to the ending, how to end a song, etc. But before that, you have to learn about something which I haven't taught you earlier. This is actually something that beginning-level musicians learn, and you'll need to know it in order to make songs more exciting. What is it? Controlling the volume. [size="5"]Part I: Controlling Volume with Music Notation [size="3"]A) Volume Levels There are basically two different kinds of music levels: Piano, and Forte. Piano means soft, and Forte means loud. Yes, Piano is also what we call the instrument you can play, but try not to confuse the two. So if your music teacher tells you to "Play piano," you'll have to find out whether she means to play a piano, or to play the song soft. So that you don't get confused, I'll explain why the Piano has the same name as a volume level. When the piano was invented, it was a revolutionary keyboard where you could control the volume just by pressing soft or pressing hard. Since it could be both soft (piano) and loud (forte), it was called the pianoforte. Eventually it was shortened to piano. Okay, that's the story. Anyway, remember these four things and you'll be fine:

[bquote]Piano - Soft Forte - Loud Mezzo - Medium Issi - A word that pretty much means "very." The more "issi"s there are, the more "very"s there are.[/bquote]

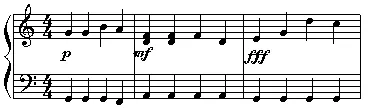

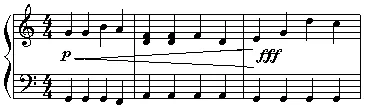

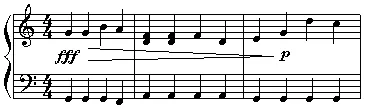

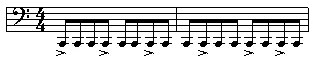

I might as well explain the word "issi". Okay, Forte means loud, right? So then what does fortissimo mean? It means "very loud." Then, what does fortississimo mean? Very very loud. Get it now? Same thing applies to piano, pianissimo, pianississimo, etc. Now I'll explain the word mezzo. It basically means medium. So if I want you to play a song at the volume level "mezzo-forte", then that means "medium-loud." That's a volume level in between mezzo-piano (medium soft) and forte. So then here's a basic succession of volume levels, from softest to loudest: Pianississimo Pianissimo Piano Mezzo-Piano Mezzo-Forte Forte Fortissimo Fortississimo Of course, you can have more volume levels than that, like fortississississississimo, but these are basically all the levels you'll need for now. It's hard to let you know exactly how loud the volume levels are since you're just reading an article, it's the kind of thing I have to describe in person. The volume level "piano" is represented by the letter p. Pianissimo is represented by pp. So that means pianississimo is represented by ppp, etc. The volume level "forte" is represented by an F. The word "mezzo" is represented by an m. So if you wanted to write the volume mezzo-forte, you would write MF. Here's a sample pic: Let's take a look at it. The first measure is at the volume level "piano". The second measure is changed to "mezzo forte", and then the last measure all of a sudden becomes loud at the level "fortississimo", sometimes called "triple forte" by lazy people like me. [size="3"]B) The Crescendo, Decrescendo, and other tricks In the picture above, measure one is played piano. (Not the instrument, the volume level.) All four notes in each staff are played at the same volume level. Then, all of a sudden, when you reach the second measure, it becomes louder, at the volume level mezzo forte. What if you want to make it a gradual change? For example, instead of having piano the first measure, mf the second measure, and fff the third measure, what if you just wanted it to start at piano, and gradually change to fff until the third measure? Then you use a crescendo. A crescendo sort of looks like a "less than" sign in math. ( < ) The only difference is that it is a lot wider. Here is the same picture as above, except this time there is a crescendo: So now you see that instead of playing each measure at a certain level, this one sounds better. You start at piano, and with every note, you get louder. You gradually get louder, until you reach triple forte in the beginning of the last measure. The opposite can also be done. You can gradually get softer, by drawing a decrescendo: In this example, you start loud, at fff. You gradually get softer, until you play piano at the last measure. What if you want to play one note exceptionally loud and then after that, return to the normal volume level? Use an accent. This looks like a "greater than" sign. (>). However, don't confuse an accent with a decrescendo. Just remember, if it stretches over two or more notes, it's probably a decrescendo; if it is above or below only one note, it's probably an accent. Just one of the many tricks of the trade that us musicians know. A beat such as this is usually used for action songs. To listen to it play twice, download midi1.mid using the attached resource file. Of course, there is more than one kind of accent, but maybe we'll get into that in a later article. [size="5"]Part II: Opening, building up, and ending a song [size="3"]A) Opening a song: How to introduce the theme Hold on. Before I go on to this, I want you to make sure you know what you're learning right now. Right now I'm going to talk about how to write a basic song. However, if you want to know how to write a song that can be played on the radio (popular music, etc.) then email me. Those songs use a bit of a different format. So just email me telling me the kind of format you want and if I get enough requests for it, I'll most likely write it. My email, again, is [email="Pitech@hawaii.rr.com"]Pitech@hawaii.rr.com[/email]. The format that I'll be teaching you in this article is the format you most likely will use if you want to write the background music to a game. Okay, now that that's been cleared up, why don't I get started? Remember how I taught you in previous articles that a long song is basically a theme played over and over? When you want to write a song, usually the first thing you should come up with is the theme. Once you've got the theme, then you should get started on the beginning. (Some people, including me (sometimes), write a beginning first and just wait until a theme comes to them. It doesn't really matter, different people do different things. Once again, I want to stress how writing music is almost absolute freedom, unless the type of music you can write is restricted by the people you are writing the music for. Anyway...) The beginning is usually one of these five things: (these aren't the real names for them. I couldn't remember the real names for them, so I'll make these ones up.) - Building up: This type of beginning is one where you start with something simple, say a drum solo, and then slowly the background to the theme comes in, and then more background, and then eventually the theme itself comes in. Sometimes the background (the music that would be playing in the background while the theme would be playing) is just playing by itself, then comes the bass and/or drums, then comes the main theme. There is midi1.mid in the file attached to this article, an example of one of those songs. Don't worry if it sounds crappy, I only put it together in about five minutes.

- Introducing an alternate theme: Here, you start with a different theme and slowly introduce the other theme. For example, you play another theme, and then play a part of the theme, and then play the other theme, and then play the main theme, and then the other theme, and then again, and each time you play the main theme you play it louder and place more emphasis on the main theme and less on the alternate theme. Eventually the alternate theme stops and you play the main theme all the time. These intros are usually pretty long.

- No playing around: In here, you don't do any stuff in the beginning, instead you just play the theme, with all of the background and everything, starting from the beginning. This isn't really an intro, but for some themes, it works better than any of the others. This is what you will probably use if there is no ending to your song; if it will repeat over and over.

- With a cool intro: Here, you just play a cool intro that is really short, (maybe about four measures or so) and then it builds up, and then your theme plays in full force. Ever heard the Kurt Angle theme? That's pretty much a song that's like this.

- Combinations of the Above: Combinations of the above introductions can be done. For example, you could have number 4, then number 1. I do that a lot, especially for action songs, songs for battles.

- Write volume changes

- Gradually change volume

- Write the beginnings of songs

- Write the middles of songs

- Write the endings of songs If you want to know how to write the beginnings, middles, and endings of other types of songs, like jazz, popular music, etc, then email me. My next article should probably talk about how to write a basic theme that will make the audiences go crazy. (By common sense that article should have been sent before this one...sorry!) Hasta lavista, estudiantes!