Artificial Intelligence (AI) is based on making intelligent looking decisions, for the units in our games to look intelligent they have to perform actions that seem reasonable for the situations they are in.

In a Real-Time Strategy (RTS) type game these actions would consist of moving, patrolling, avoiding obstacles, targeting enemies and pursuing them. Lets take a look at what it would take to implement each of these actions.

[size="5"]Movement

Moving, in its most basic form, consists of simply advancing from one set of coordinates to another set over a period of time. This can be performed easily by finding a distance vector and multiplying it by the speed the unit is moving and the time since we last calculated the position.

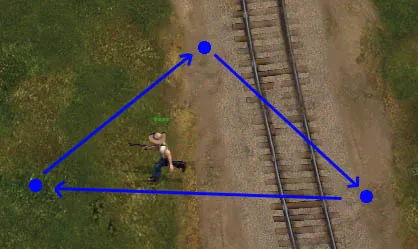

Because we are working from a mouse based input system, we don't expect the user to have to make all the movements around obstacles like they would in a joystick or first-person shooter. The way to keep the user from having to click their way around obstacles is to create an action queue so that we can have more than one action in a row completed. This way if a path has to avoid an obstacle we can add the additional paths in front of the final destination to walk the unit around the obstacle without player intervention.

[size="5"]Patrolling

Patrolling consists of moving to a series of specified positions in order. At the time when a unit has moved to a destination and has nowhere else to go, we can compare his current position to his list of patrol points and set a new destination to the one after where he is closest to.

There isn't a lot to this, but having units moving on the screen, as opposed to standing still and waiting, makes the world look a lot more alive and gives them a lot less chance of being snuck up on and catching intruders.

[size="5"]Obstacle Avoidance

Avoidance algorithms require the understanding of how your maps are going to work and how you want your units to interact with them while moving around. In our case we are going to assume an outdoor environment with relatively small and simple obstacles such as small buildings and objects. We will also assume that you cannot go inside an obstacle and that obstacles are convex polygons with 4 vertices.

In an environment such as this we are mostly dealing with open movement and obstacles that have to be avoided can be with only 1-2 avoidance movements.

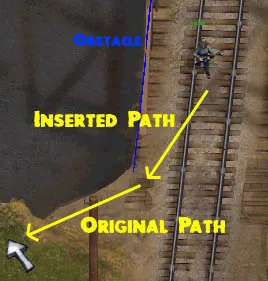

In the example to the left we have a very thin 4 point poly that is between the unit and the destination. In this case we move away from the closest vertex to the destination and move several units away in the perpendicular angle from the unit's collision. This gives us the buffer space we need to move around the obstacle.

Obstacle avoidance has to be determined by the type of the obstacles you are going to be providing. In this simple example we are going to use convex 4 point polygons, which will usually be in a diamond or square shape. Because of these obstacle limitations we can simply find the edge closest to the destination which the unit trying to get to and move out from the obstacle a little thereby creating a simple way to avoid obstacles which works fairly well as long as obstacles dont get too close together.

When you want to get into some more advanced path finding algorithms, you should look into A*, which is a popular algorithm for finding the shortest path through very maze-like areas. Beyond A* there are various steering algorithms for gradually moving around obstacles and other more hard-coded situations such as creating funneling intersections that can be used to get to different areas of the map.

[size="5"]Targeting Enemies

Targeting for other units will greatly depend on what you want your player to be doing in your game. You may want your player's units to automatically fire on enemies they see, so that player can devote themselves to the big picture. You may want your units to only attack if specifically told to keep your player's attention on the units and their surroundings.

Either way, you will want your enemies to be on the look out for the player's units to provide the challenge of on-the-ball enemies.

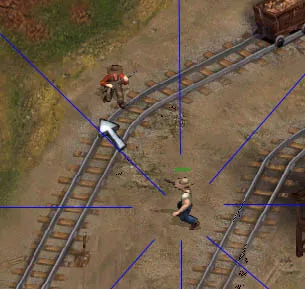

In a situation where you have split up your directions 8 ways, you can assume that for a unit to be facing another unit, within vision range, they must be either directly in front of the unit or in one of the adjacent directions. A simple test to determine if the unit is within maximum sight distance and is in one of these three directions from the unit can give you good result with a minimal amount of time to test cases.

Of course you will want to add in a test for obstacles to see if the units are blocked, most likely you can use the same test for obstacle avoidance for this, as you usually either have a clear path or not . Adding in height to visibility testing will of course totally change the nature of these tests, but that is for another article.

[size="5"]Pursuit

Once your enemies have found a target, you won't want them to just wander around aimlessly if they lose sight of their prey. At this point you need to make a choice about how you wish to handle your searching though. Up until now we have only talked about spotting units based on actually being able to see them. In some cases this may get a little tricky when pursuing an enemy, so you may opt to cheat and just set the destination of the unit being tracked as the tracker's destination.

If you wish to keep things more realistic and do less "cheating", then you need to store the last position the target was seen in to give a place to start searching for them. For our example we will just take a random search approach. First you would set the last position the target was seen as the first destination. Then as the next destination you would make a random distance in the direction that the target was originally from the unit before he lost sight of the target.

In this way we assume that the target ran away from the unit and if we are correct, the unit will hopefully find him quickly after passing the first destination. In case the unit did not find his target, we can make a back up plan of setting a patrol at random distances around where the first destination was. So the unit will go back to the spot his target was last seen and will walk in a pattern searching for him.

While this doesn't cover a lot of possibilities, it does give us a reasonable response given the situation.

[size="5"]Conclusion

The secret to implementing all game AI is the understanding the cases you are trying to deal with and the results of what you want it to look like. If you can picture what you want the actions to look like and formulate an algorithm to make them turn out that way you are 90% of the way done. However the last 10%, getting it to work, can easily take 10 times as long as figuring out how to do it...

[email="ghowland@lupinegames.com"]-Geoff Howland[/email]

Lupine Games

The first article: Practical Guide to Building a Complete Game AI: Volume I

A Practical Guide to Building a Complete Game AI: Volume II

Do you see issues with this article? Let us know.

Part 2 covers unit goals and pathfinding.

Advertisement

Recommended Tutorials

Advertisement

Other Tutorials by Myopic Rhino

27041 views

24418 views

Advertisement