Second Age

There are many ways to classify RTS history. For the sake of this article, we'll assume that by "second age", we refer to games that were released several months after Warcraft: Orcs and Humans. These were developed with sufficient observation of the multiplayer interactions that were first showcased in Warcraft, and come with a (perhaps naive) understanding of how multiplayer has affected the RTS as a genre. In many ways, changing the focus of the RTS genre from that of a conventional single player experience to a competitive e-sport started when players had a chance to play games against one another, and how game developers reflected upon this experience. It shaped and defined new visions and new objectives for the developers, and was the underlying metric against which most decisions to come would be matched. We've already observed that Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty was quite a strong precursor that spawned an entire genre, and it was so meaty there was little a single player game could hope to further achieve. Warcraft: Orcs and Humans was built as both a testament to Dune II (revered by all of the development team if Patrick Wyatt is to be believed) and as an attempt to stretch the possibilites of this game to the multiplayer scene, without fore-knowledge of just how much untapped potential there was along that thread. Building upon the Multiplayer experience and shifting production focus made sense: On the one hand, there didn't seem to be that much that could be added/changed to the then-winning formula of the RTS, and multiplayer had already proved it could garner its own share of the sales pot as a retail box feature. It wasn't a lack of inspiration, but an actual opportunity that helped crystallize the RTS as it was. Developers did not seek to be inventive in how the RTS mechanics worked because there was simply too much work to be done to fully bring multiplayer to the next step: making it a sport (or Chess 2.0).

Warcraft II

Warcraft II is a very interesting installment of the RTS genre. Unlike all previous games, it was built with about 1 year of experience observing players interacting with the first multiplayer RTS. Blizzard's bet clearly paid off by then: competition had brought a whole new dimension to the RTS genre. They were probably the ones with the best insight into how multiplayer had modified the RTS scene and quickly capitalized on their advantage by launching a title that was clearly a defining moment in the RTS history. It is worth to mention that Command & Conquer was released earlier and received much praise for its multiplayer support, and storyline implementation (actual movies showcasing then-Westwood employees). To justify my choice of moving forward with Warcraft II, I'll only quote this:

" By all accounts, Command & Conquer (C&C) was an immediate and unmitigated success when it was released in late 1995. It spawned one of the most lucrative series in videogame history, and its title has become synonymous with real-time strategy (RTS). Yet, the basis of the game was not original. Dune II, from the same developer, had previously established the RTS genre, and C&C was almost identical in many respects. What made C&C such a sensation was its refinement of Dune II's gameplay ideas with the addition of several key innovations, which set the standard for all games of the genre to come. Internet play and varied styles of play between the different armies in the game were some of the important advances that are now fundamental to RTS. Furthermore, C&C's flaws clearly showed some areas in which improvement was possible."

Pacing

With people setting up for multiplayer sessions, it soon became apparent that Warcraft: Orcs and Humans took too much time off people's phone lines. Blizzard felt they had a chance to increase popularity of the genre by making the game faster (allowing more players to play, and more games to actually be completed). As a result, they've made the game faster in many ways, most notably through unit movement (which had both an effect on economy and combat). The expected outcome was to make games shorter and insure people could play more often, but there were also a few byproducts that were introduced by this new "pacing": Because the game was faster, player mastery over the input became critical once more. The game slowly shifted away from a tactical game (such as Warcraft: Orcs and Humans) and entered the realm of the dreaded APM (Actions per minute). Here, the problem was not necessarily UX (such as in Dune II), as the game effectively provided tools developed during Warcraft: Orcs and Humans (multi-selection, command hotkeys, control groups), but the effect was similar: an average player would feel there was too much to do and would need to prioritize the most meaningful micro-management-intensive actions at any given time.

Streamlined

In Warcraft 2, time is streamlined. Actions are meant to be fast-paced, putting more emphasis on player execution than strategy. It puts the player under rush and leads the player with the most nerves to victory. Units are more expandable, and the unit cap has been raised, shifting focus to constant streams of military production. Economic upgrades also reduce the need for peasants by a bit, further focusing on military production. To accomodate this slight shift, the multi-selection tool is extended to 9 units to improve maneuverability, and single-click actions (right clicking) allows for quick orders. The concept of Roads is removed from the game altogether, removing building placement restrictions. With the inclusion of watch-towers, which are defensive buildings, it is now possible to guard any specific position on the map with extra support. Even offensively when needed. To support "free-building", it is now possible to erect town halls and some proxy-buildings that allow resource gathering, reducing/annihilating the need for supply lines at a very cheap price. Concentration of forces becomes more prevalent as a result. Although most of these changes appear simple, they change the game's nature: Where Warcraft: Orcs and Humans was all about trying to protect long supply lines of peasants cutting distant forests or fetching gold from remote gold mines, the game now starts to look more like "expansions" (small bases) with economical or military focus. It teaches the player that this is the way to play the game now, and it looks nothing like the previous game.

Fog of War 2.0: The "Shroud" regrows...

Yet, there are a few innovations in Warcraft II. One of the most important is the Shroud. Up to this point, most games dealing with "fog of war" only gave the impression of the unknown. The map was covered in darkness, but as soon as a unit revealed a portion of the map, it would remain visible forever. The original fog of war was more about discovering the "landscape" and much less so keeping tabs on enemy movement.  The Shroud, or fog of war 2.0, actually regrows when there are no units with line of sight to a portion of the map. The landscape itself remains, as this is fairly static, but the knowledge of enemy troops and buildings becomes vague: units are no longer shown, and buildings only reveal the last known status of a given area (disregarding any changes that may have been operated later). This is an ideal inclusion for a multiplayer game as it forces players to spread their forces to have the information they need. They are likely to spy on their enemies to know what's coming their way, and it makes it that much better. It is such a good system in fact that it will remain largely unchanged until Starcraft II: Wings of Liberty (but more on that later).

The Shroud, or fog of war 2.0, actually regrows when there are no units with line of sight to a portion of the map. The landscape itself remains, as this is fairly static, but the knowledge of enemy troops and buildings becomes vague: units are no longer shown, and buildings only reveal the last known status of a given area (disregarding any changes that may have been operated later). This is an ideal inclusion for a multiplayer game as it forces players to spread their forces to have the information they need. They are likely to spy on their enemies to know what's coming their way, and it makes it that much better. It is such a good system in fact that it will remain largely unchanged until Starcraft II: Wings of Liberty (but more on that later).

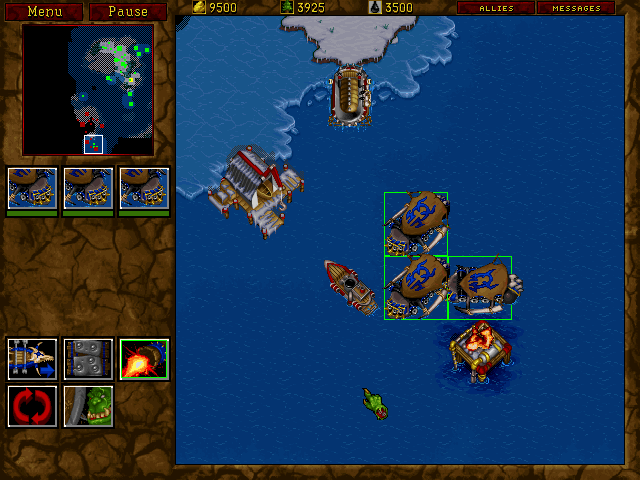

One too many resources? - The Black Gold Case

Since the dawn of time... well not really, but since Warcraft: Orcs and Humans, the idea of more resources had been considered. Dune II had only 1: spice melange. Warcraft: Orcs and Humans had 2, but actually had 3 during development (the third one being rocks I believe). The development team behind Warcraft II chose to move forward with the idea of a third resource, one that would unlock another facet of the game. Their choice was to have an "advanced" resource only available in the mid to late-game that would provide access to more advanced units (naval) and unit upgrades (some of which affect non-naval units).  Unlike Age of Empires, in order to erect a fleet, a player would need to have control over water before being able to claim their right to it, and tentatively, the first player to dominate the seas could deny access to his opponent and perform interdiction missions to raid its borders. The only means to escape this would be to utilize air units. This was a tricky move given that oil was not necessarily employed to build more powerful units, but rather, to unlock a different layer of the terrain which was, in several maps, optional. This rendered oil somewhat superfluous. Its legacy however, is that it inspired the concept of a resource that would only become available with some form of investment, and would be helpful for more advance units. Though this can arguably said of lumbers (used to build archers) there was no real form of investment, and it was already necessary for building construction. This concept would later become used in other games such as Starcraft (Vespene Gas).

Unlike Age of Empires, in order to erect a fleet, a player would need to have control over water before being able to claim their right to it, and tentatively, the first player to dominate the seas could deny access to his opponent and perform interdiction missions to raid its borders. The only means to escape this would be to utilize air units. This was a tricky move given that oil was not necessarily employed to build more powerful units, but rather, to unlock a different layer of the terrain which was, in several maps, optional. This rendered oil somewhat superfluous. Its legacy however, is that it inspired the concept of a resource that would only become available with some form of investment, and would be helpful for more advance units. Though this can arguably said of lumbers (used to build archers) there was no real form of investment, and it was already necessary for building construction. This concept would later become used in other games such as Starcraft (Vespene Gas).

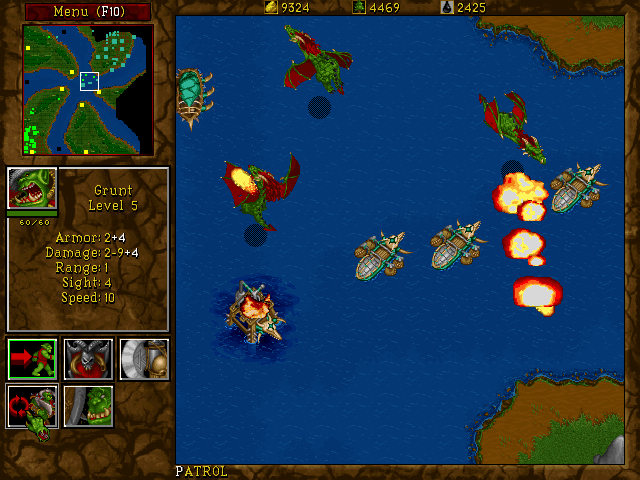

The Z Axis! - Air units

Air units really made their debut in Warcraft II. They allowed to trade high amounts of resources to take advantage of free-movement. This allowed both access to very efficient scouting units (Zeppelins) and all-terrain capable strike units (dragons, gryphons).  The air units also helped counter-balance the naval units' economic issue (can't build some if you can't control the sea first), but they also allowed to bypass terrain collisions and strike from unexpected angles, fast, and relatively unscathed when desired. This greatly diminished the value of ground units (though they were still stronger on average in 1v1 encounters) and improved the value of mixed arms tactics. Air units have since been included in many RTS games (specifically those that value mixed arms tactics over maneuverability).

The air units also helped counter-balance the naval units' economic issue (can't build some if you can't control the sea first), but they also allowed to bypass terrain collisions and strike from unexpected angles, fast, and relatively unscathed when desired. This greatly diminished the value of ground units (though they were still stronger on average in 1v1 encounters) and improved the value of mixed arms tactics. Air units have since been included in many RTS games (specifically those that value mixed arms tactics over maneuverability).

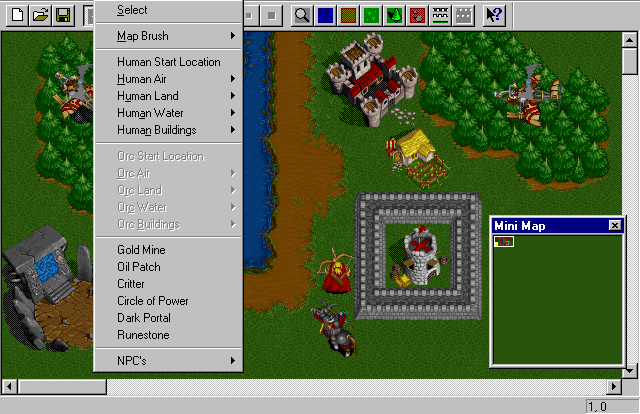

Map Editor

One of the key elements bundled along with Warcraft II was the Level Editor: a simple yet very efficient means to create additionnal levels for the game (playable in multiplayer) which would make the game last much longer. In a Blizzard-style RTS, the level-editor became de-facto (Starctaft, Warcraft III and Starcraft II replicated this) often leading to very popular maps that would evolve into spinoff games/genres (DOTA/LOL or the MOBA genre is often said to be born from a Warcraft III mod).

Starcraft

Starcraft is a personal favorite, so I'll do my best and try to remain grounded. It was a great, acclaimed game when it was released, and to this day, it spawned the only Blizzard RTS series that is still active (Warcraft's last installment was Warcraft III, and Blizzard has demonstrated no interest in pursuing the series, finding its RPG elements much more interesting to exploit). Asymmetry

Starcraft's obvious legacy is pure assymetry. Unlike previous installments of the RTS genre that used a set of similar units or at least economic precepts, Starcraft breaks several rules to bring alive 3 radically different factions (which must've been a nightmare to try and balance, as would attest all of the patches it has endured). This metamorphosis is so deeply encroached in the design that even the "builder" or "economic" units vary greatly. For example, while the Terran SCV (builder) is fairly mainstream (stays at construction site for the duration of the construction, and then resumes its duties), the Protoss Probe can start the construction of buildings and immediately leave while the Zerg's Drone actually needs to be sacrificed in the process to generate a living building. Furthermore, each faction has placement limitations that are unique to them (Terrans can build anywhere, Protoss need to setup a power network of Pylons, and Zergs must extend their creep). Their Unit capacity is also determined by different means. The Terrans must build a structure that is specifically used to improve their food count, whereas the Protoss have bundled this ability together with their Pylon (already used for placement limitations) and the Zerg have simply tasked one of their units (the Overlord) with production the necessary sustainment for their army.  Lastly, units from each faction differ also in how they handle damage: The Terrans take damage, and beyond a certain threshold, their structures will start to burn. They can repair damage with their builder unit but only for structures and vehicles, and they have a dedicated medic unit to heal wounds of their organic units. The Protoss have shields which regenerate very quickly (particularly useful between encounters), but once their life is damaged, they can't heal it back to full. The Zergs are all Organic units and have a persistent (although slow) regeneration rate which allows them to run interference and perform hit-and-run tactics more efficiently. Not only do they not share any unit, but all of their units are functionally different: The basic Terran unit is actually a ranged unit (the Marine) whereas the Protoss field a formidable melee unit (the Zealot) and yet the Zergs resort to quantity (2 Zerglings in the same egg). Their tech-tree is altogether different, and "Tiers" are experienced through different means: The Terrans can attach specific add-ons to their buildings (comsat, machine shop, etc.) to unlock specific upgrades and units. The Protoss rely strongly upon building inter-dependancy (need X to build Y). The Zergs must upgrade their Hive to higher levels in order to unlock further buildings. Overall, each faction feels nothing alike, and it is very hard for a player that has experience with a single faction to know what to expect from his opponents. It emphasizes play experience and planning over tactics but is still largely thrumped by APM...

Lastly, units from each faction differ also in how they handle damage: The Terrans take damage, and beyond a certain threshold, their structures will start to burn. They can repair damage with their builder unit but only for structures and vehicles, and they have a dedicated medic unit to heal wounds of their organic units. The Protoss have shields which regenerate very quickly (particularly useful between encounters), but once their life is damaged, they can't heal it back to full. The Zergs are all Organic units and have a persistent (although slow) regeneration rate which allows them to run interference and perform hit-and-run tactics more efficiently. Not only do they not share any unit, but all of their units are functionally different: The basic Terran unit is actually a ranged unit (the Marine) whereas the Protoss field a formidable melee unit (the Zealot) and yet the Zergs resort to quantity (2 Zerglings in the same egg). Their tech-tree is altogether different, and "Tiers" are experienced through different means: The Terrans can attach specific add-ons to their buildings (comsat, machine shop, etc.) to unlock specific upgrades and units. The Protoss rely strongly upon building inter-dependancy (need X to build Y). The Zergs must upgrade their Hive to higher levels in order to unlock further buildings. Overall, each faction feels nothing alike, and it is very hard for a player that has experience with a single faction to know what to expect from his opponents. It emphasizes play experience and planning over tactics but is still largely thrumped by APM...

Food Cost

A small case can be made about "food cost". Though each faction deals with it differently, the system itself actually changed across the board. Unlike previous installments, each unit has a unique food cost. A Zealot, for example, is worth 2 food, whereas a Marine is worth only 1, and Zerglings are worth 0.5. Though this may appear as a small change, it changes the game by a wide margin. The problem with earlier titles is that it was actually preferable to save on resources and max the food count with higher tier units (just ogres or knights in Warcraft II, for example, was strictly better than just grunts or footmen).  An adjusted food count changes that by making each unit worth exactly what it should be, and this encourages players not to hold back: when a player fields a 200 food count army he is a formidable opponent, regardless of what tier they are in. And just because his opponent can field 150 food with strictly superior units doesn't mean he has any chance to win the encounter. The main advantage of this system is that lower-tier units remain relevant throughout the game match, and the encounter feels less like a tech-race to the best unit and more like a game of blitz rock-paper-scissor. Players need to open up their options and retain an ability to shift production focus at a moment's notice to better counter their enemies. Siege tanks, for example, are a formidable threat against ground units and can be fielded in numbers to secure a win, but they still need the support of marines to prevent zergling swarms from rushing in, or air units from dispatching them. No unit thrumps it all.

An adjusted food count changes that by making each unit worth exactly what it should be, and this encourages players not to hold back: when a player fields a 200 food count army he is a formidable opponent, regardless of what tier they are in. And just because his opponent can field 150 food with strictly superior units doesn't mean he has any chance to win the encounter. The main advantage of this system is that lower-tier units remain relevant throughout the game match, and the encounter feels less like a tech-race to the best unit and more like a game of blitz rock-paper-scissor. Players need to open up their options and retain an ability to shift production focus at a moment's notice to better counter their enemies. Siege tanks, for example, are a formidable threat against ground units and can be fielded in numbers to secure a win, but they still need the support of marines to prevent zergling swarms from rushing in, or air units from dispatching them. No unit thrumps it all.

Tiered Logic

Starcraft has a "Tiered Logic" where there are logical steps to take in order to progress along any axis of the tech tree. One of its key tools is the inclusion of a tiered resource: The Vespene Geyser (Vespere Gas). Unlike previous installements that included secondary resources such as "Wood", the Vespene Geysers require a hefty investment in resource and time to unlock (Refinery) and have a much more limited income (maxed output with 3 worker units) capacity. The ramifications of these limitations are numerous, but at its core, it permits (and dictates) the concept of a Tiered Logic. Units that require only minerals to build (and are built from buildings that require only minerals) then obviously become the most readily available (tier 1) and any unit that requires a single building investent of Gas or has a limited Gas cost itself becomes a slightly more important investment (tier 2). Likewise, further investments of Gas (either through multiple buildings, or higher gas cost) relegate units to further tiers along the tree. These tiers are a balancing tool that players can learn to rely on: they know, for a fact, that unit X cannot appear before Y units of time into the game, simply because of the logical steps that need to be taken towards getting the necessary gas investment to get there. Furthermore, it ensures that player can strategize and optimize their resource collection to take advantage of this: a well-prepared player can shift to tier 2 units much more efficiently than a rookie, and can oftentimes claim a decisive advantage for doing so at the right time.  Knowing "when" to build a refinery, and how many to build becomes key to mastering that tiered logic. The elaborate tech tree of each faction creates a large number of permutations and an acute observer may be able to tell a player's strategy just by the timing of refineries being built, or the amount of units shifting from minerals to gas. While previous installments sometimes had forced tiers (upgrading the townhall in Warcraft II for example) the tiered logic approach is much more organic and opens up more possibilities. Coupled with actual unit food, this gives players several opportunities and freedom of choice on whether to evolve at all or use of the lower-tier tactics (bio-ball for example).

Knowing "when" to build a refinery, and how many to build becomes key to mastering that tiered logic. The elaborate tech tree of each faction creates a large number of permutations and an acute observer may be able to tell a player's strategy just by the timing of refineries being built, or the amount of units shifting from minerals to gas. While previous installments sometimes had forced tiers (upgrading the townhall in Warcraft II for example) the tiered logic approach is much more organic and opens up more possibilities. Coupled with actual unit food, this gives players several opportunities and freedom of choice on whether to evolve at all or use of the lower-tier tactics (bio-ball for example).

Battle.net

Starcraft, unlike its predecessors, was released through Battle.net, Blizzard's online gaming platform. It allowed several multiplayer "metagame" features such as ladders (which would keep scores of win/losses/draws for individual players). It was also a very efficient platform to match-up 8 players together and provided a number of game modes (including custom scenario). From simply joining up with a friend through dialup, players could now jump into the fray and faceoff with up to 7 random strangers (or friends) from the internet without having to wait. There was always someone online to play against and playing Starcraft no longer required tuning one's agenda with friends'.  This contributed to the then rising phenomenon of playing against or with strangers. This also confronted more players to the "online norm" as far as playing skill was concerned, instead of focusing on small pockets of players that would play locally against one another. In essence, this contributed to strategies emerging at an alarming rate, then shifting what many would refer to as the "metagame" (strategies that tend to be dominant solely because certain strategies are in vogue amongst the large populace). For example, building a supply depot close by a ramp to limit access was not necessarily considered a "good move" by gameplay mechanics' standards, but after a lot of players followed the 4, 5 or 6 pool rush tactics, it became an invaluable means of breaking early zerging rushes. Likewise, dark templars are a very circumstancial unit, but they became much more potent against volley of protoss players that would play "4 Gate Goon". Devoid of the metagame that came along with Battle.net's existence, all of these are doubtful approaches, but in the context of a globalized gaming hub, players were much more likely to face similar strategies reccurently and devise plans to defeat them rather than optimize their "general" strategy.

This contributed to the then rising phenomenon of playing against or with strangers. This also confronted more players to the "online norm" as far as playing skill was concerned, instead of focusing on small pockets of players that would play locally against one another. In essence, this contributed to strategies emerging at an alarming rate, then shifting what many would refer to as the "metagame" (strategies that tend to be dominant solely because certain strategies are in vogue amongst the large populace). For example, building a supply depot close by a ramp to limit access was not necessarily considered a "good move" by gameplay mechanics' standards, but after a lot of players followed the 4, 5 or 6 pool rush tactics, it became an invaluable means of breaking early zerging rushes. Likewise, dark templars are a very circumstancial unit, but they became much more potent against volley of protoss players that would play "4 Gate Goon". Devoid of the metagame that came along with Battle.net's existence, all of these are doubtful approaches, but in the context of a globalized gaming hub, players were much more likely to face similar strategies reccurently and devise plans to defeat them rather than optimize their "general" strategy.

Balance & Execution

There's an undeniable portion of "new" in Stacraft. The unique brand, assymetrical design and tiered logic prove this. But Starcraft shines mostly by its brilliant balance. Coming along assymetrical design came the arduous task of unit balancing: How could matches be kept "balanced" all the while offering drastically different options? Never before had an RTS put so much emphasis on its Patches. Frequently, patches would be released to counter emerging strategies in the metagame, and insure that skillful play was always encouraged. But the core release itself was already quite a piece of work. The player community helped shape this balance, always seeking ways to break it (reverse-engineering the exact calculations behind the game). In the end, though Starcraft remains imperfect, it is very close to an evenly matched game, and player input has so much power on that balance that it is almost impossible to abuse dominant strategies: there's a counter to everything, you just need to have sufficient experience to know what it is. As a result, Starcraft is another shining example of execution. I would even argue that its popularity stemmed from the mere fact it was closer to chess than any other RTS before its time (although, arguably, an asymmetric version of chess such as Tafl). Unlike most predecessors, Starcraft handles damage in a very deterministic way, making each outcome known, and limiting hidden information to the fog of war / shroud. This minimizes the amount of gambling and emphasizes the value of min/maxing. One needs only venture at TeamLiquid to notice how much thought has been put towards trying to find the best counter to everything. Determining when to get these precious weapon upgrades, for example, can be quantified almost easily!

Never before had an RTS put so much emphasis on its Patches. Frequently, patches would be released to counter emerging strategies in the metagame, and insure that skillful play was always encouraged. But the core release itself was already quite a piece of work. The player community helped shape this balance, always seeking ways to break it (reverse-engineering the exact calculations behind the game). In the end, though Starcraft remains imperfect, it is very close to an evenly matched game, and player input has so much power on that balance that it is almost impossible to abuse dominant strategies: there's a counter to everything, you just need to have sufficient experience to know what it is. As a result, Starcraft is another shining example of execution. I would even argue that its popularity stemmed from the mere fact it was closer to chess than any other RTS before its time (although, arguably, an asymmetric version of chess such as Tafl). Unlike most predecessors, Starcraft handles damage in a very deterministic way, making each outcome known, and limiting hidden information to the fog of war / shroud. This minimizes the amount of gambling and emphasizes the value of min/maxing. One needs only venture at TeamLiquid to notice how much thought has been put towards trying to find the best counter to everything. Determining when to get these precious weapon upgrades, for example, can be quantified almost easily!

Culmination

The following years would bring us many quality games, and exciting experiences. For the most part, however, it is hard to determine what trully distinguishes Starcraft I from Starcraft II, Dune 2000 from Emperor Dune, or even Ages of Empire from most of the aforementionned games. Though the branding, visual quality and feel of these games would feel drastically different, they would remain mechanically the same.

i see you never played Dark Reign from 1997... wich outshines starcraft or TA in so many aspects of multiplayer and AI.