Hey Folks ![]()

Welcome to part two of the series "The Entity-Component-System". As always you can checkout the original post here.

In my last post (The Entity-Component-System - An awesome game-design pattern in C++ (Part 1)), I talked about the Entity-Component-System (ECS) design pattern and my own implementation. Now I want to show you how to actually use it to build a game with it. If you not already have seen it, check out what kinda game I built with the help of my ECS.

I will admit this does not look much, but if you ever had build your own game without help of a big and fancy game engine, like Unity or Unreal, you might give me some credit here ![]() So for the purpose of demonstrating my ECS I simply just need that much. If you still have not figured out what this game (BountyHunter) is about, let me help you out with the following picture:

So for the purpose of demonstrating my ECS I simply just need that much. If you still have not figured out what this game (BountyHunter) is about, let me help you out with the following picture:

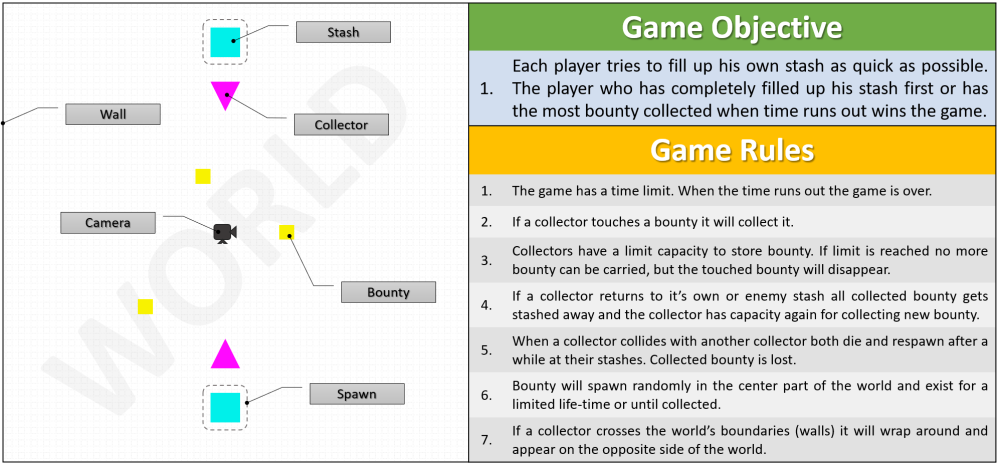

Figure-01: BountyHunter objective and rules.

The picture on the left may look familiar as it is a more abstract view of the game you saw in the video clip. Focus is laid on game entities. On the right hand side you will find the game objective and rules. This should be pretty much self-explanatory. As you can see we got a bunch of entity types living in this game world and now you may wonder what they are actually made of? Well components of course. While some types of components are common for all this entities a few are unique for others. Check out the next picture.

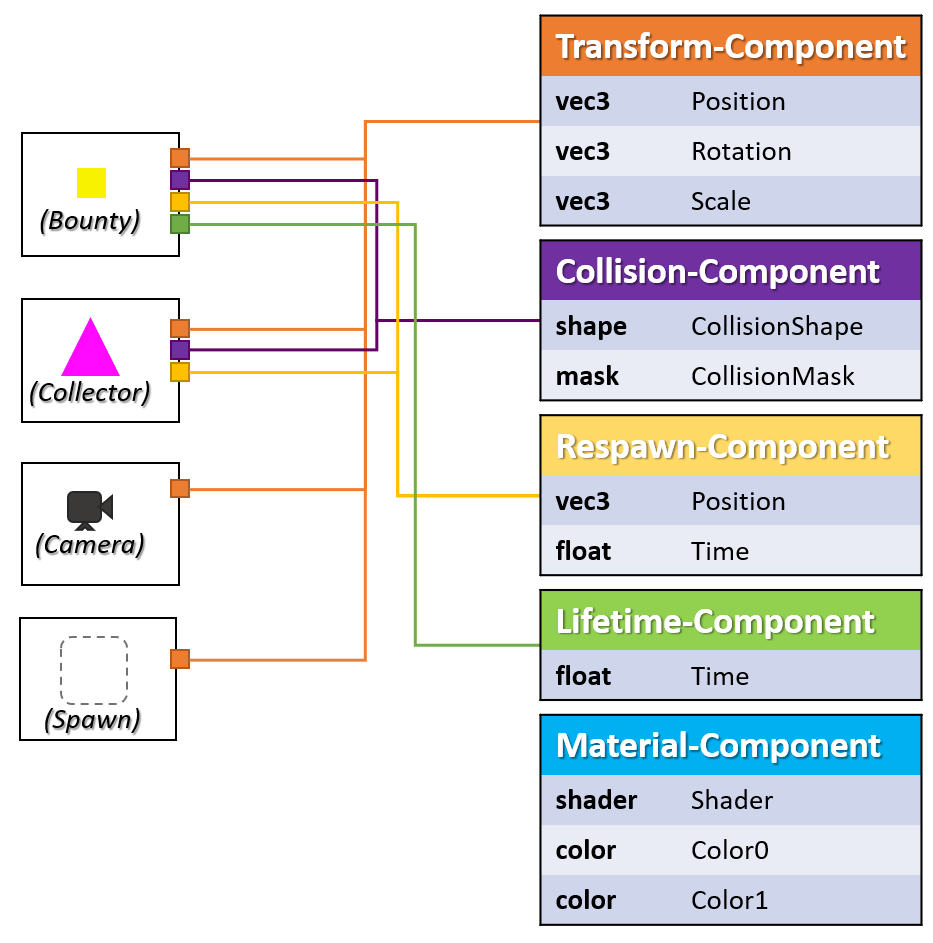

Figure-02: Entity and their components.

By looking at this picture you can easily see the relation between entities and their components (this is not a complete depiction!). All game entities have the Transform-Component in common. Because game entities must be somewhere located in the world they have a transform, which describes the entities position, rotation and scale. This might be the one and only component attached to an entity. The camera object for instance does require more components especially not a Material-Component as it will be never visible to the player (this might not be true if you would use it for post-effects). The Bounty and Collector entity objects on the other hand do have a visual appearance and therefore need a Material-Component to get displayed. They also can collide with other objects in the game world and therefore have a Collision-Component attached, which describes their physical form. The Bounty entity has one more component attached to it; the Lifetime-Component. This component states the remaining life-time of a Bounty object, when it’s life-time is elapsed the bounty will fade away.

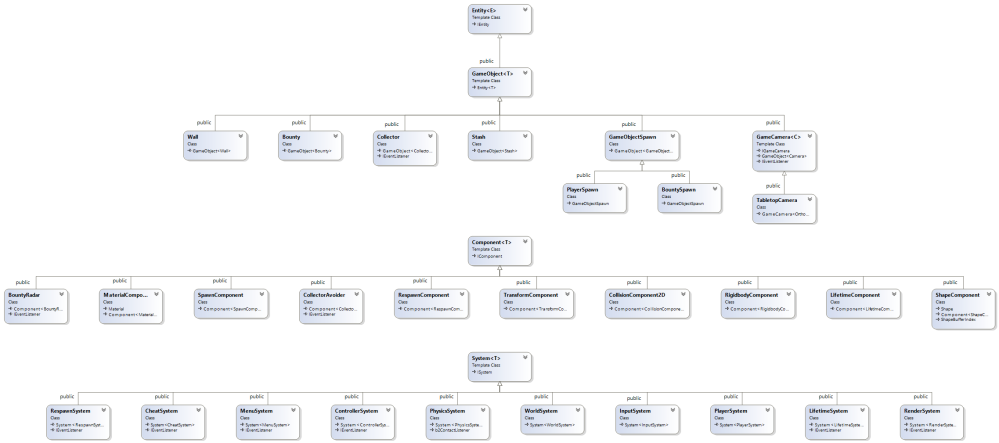

So what’s next? Having all these different entities with their individual gathering of components does not complete the game. We also need someone who knows how to drive each one of them. I am talking about the systems of course. Systems are great. You can use systems to split up your entire game-logic into much smaller pieces. Each piece dealing with a different aspect of the game. There could or actually should be an Input-System, which is handling all the player input. Or a Render-System that brings all the shapes and color onto screen. A Respawn-System to respawn dead game objects. I guess you got the idea. The following picture shows a complete class-diagram of all the concrete entity, component and system types in BountyHunter.

Figure-03: BountyHunter ECS class-diagram.

Now we got entities, components and system (ECS), but wait there is more.. events! To let systems and entities communicate with each other I provided a collection of 38 different events:

GameInitializedEvent GameRestartedEvent GameStartedEvent

GamePausedEvent GameResumedEvent GameoverEvent GameQuitEvent

PauseGameEvent ResumeGameEvent RestartGameEvent QuitGameEvent

LeftButtonDownEvent LeftButtonUpEvent LeftButtonPressedEvent

RightButtonDownEvent RightButtonUpEvent RightButtonPressedEvent

KeyDownEvent KeyUpEvent KeyPressedEvent ToggleFullscreenEvent

EnterFullscreenModeEvent StashFull EnterWindowModeEvent

GameObjectCreated GameObjectDestroyed PlayerLeft GameObjectSpawned

GameObjectKilled CameraCreated, CameraDestroyed ToggleDebugDrawEvent

WindowMinimizedEvent WindowRestoredEvent WindowResizedEvent

PlayerJoined CollisionBeginEvent CollisionEndEvent And there is still more , what else did I need to make BountyHunter:

- general application framework – SDL2 for getting the player input and setting up the basic application window.

- graphics – I used a custom OpenGL renderer to make rendering into that application window possible.

- math – for solid linear algebra I used glm.

- collision detection – for collision detection I used box2d physics.

- Finite-State-Machine – used for simple AI and game states.

Obviously I am not going to talk about all these mechanics as they are worth their own post, which I might do at a later point But, if your are enthusiastic to get to know anyway I won’t stop you and leave you with this link. Looking at all the features I mentioned above you may realize that they are a good start for your own small game engine. Here are a few more things I got on my todo-list, but actually did not implement just because I wanted to get things done.

- Editor – an editor managing entities, components, systems and more

- Savegame – persist entities and their components into a database using some ORM library (e.g. codesynthesis)

- Replays – recoding events at run-time and replay them at a later point

- GUI – using a GUI framework (e.g. librocket) to build an interactive game-menu

- Resource-Manager – synchronous and asynchronous loading of assets (textures, fonts, models etc.) through a custom resource manager

- Networking – send events across the network and setup a multiplayer mode

I will leave these todo’s up to you as a challenge to proof that you are an awesome programmer ![]()

Finally let me provide you some code, which demonstrates the usage of the my ECS. Remember the Bounty game entity? Bounties are the small yellow, big red and all in between squares spawning somewhere randomly in the center of the world. The following snipped shows the code of the class declaration of the Bounty entity.

// Bounty.h

class Bounty : public GameObject<Bounty>

{

private:

// cache components

TransformComponent* m_ThisTransform;

RigidbodyComponent* m_ThisRigidbody;

CollisionComponent2D* m_ThisCollision;

MaterialComponent* m_ThisMaterial;

LifetimeComponent* m_ThisLifetime;

// bounty class property

float m_Value;

public:

Bounty(GameObjectId spawnId);

virtual ~Bounty();

virtual void OnEnable() override;

virtual void OnDisable() override;

inline float GetBounty() const { return this->m_Value; }

// called OnEnable, sets new randomly sampled bounty value

void ShuffleBounty();

}; The code is pretty much straight forward. I’ve created a new game entity by deriving from GameObject<T> (which is derived from ECS::Entity<T>), with the class (Bounty) itself as T. Now the ECS is aware of that concrete entity type and a unique (static-)type-identifier will be created. We will also get access to the convenient methods AddComponent<U>, GetComponent<U>, RemoveComponent<U>. Besides the components, which I show you in a second, there is another property; the bounty value. I am not sure why I did not put that property into a separate component, for instance a BountyComponentcomponent, because that would be the right way. Instead I just put the bounty value property as member into the Bounty class, shame on me. But hey, this only shows you the great flexibility of this pattern, right? ![]() Right, the components …

Right, the components …

// Bounty.cpp

Bounty::Bounty(GameObjectId spawnId)

{

Shape shape = ShapeGenerator::CreateShape<QuadShape>();

AddComponent<ShapeComponent>(shape);

AddComponent<RespawnComponent>(BOUNTY_RESPAWNTIME, spawnId, true);

// cache this components

this->m_ThisTransform = GetComponent<TransformComponent>();

this->m_ThisMaterial = AddComponent<MaterialComponent>(MaterialGenerator::CreateMaterial<defaultmaterial>());

this->m_ThisRigidbody = AddComponent<RigidbodyComponent>(0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0001f);

this->m_ThisCollision = AddComponent<CollisionComponent2d>(shape, this->m_ThisTransform->AsTransform()->GetScale(), CollisionCategory::Bounty_Category, CollisionMask::Bounty_Collision);

this->m_ThisLifetime = AddComponent<LifetimeComponent>(BOUNTY_MIN_LIFETIME, BOUNTY_MAX_LIFETIME);

}

// other implementations ... I’ve used the constructor to attach all the components required by the Bountyentity. Note that this approach creates a prefabricate of an object and is not flexible, that is, you will always get a Bounty object with the same components attached to it. Where this is a good enough solution for this game it might be not in a more complex one. In such a case you would provide a factory that produces custom tailored entity objects.

As you can see in the code above there are quite a few components attached to the Bounty entity. We got a ShapeComponent and MaterialComponent for the visual appearance. A RigidbodyComponent and CollisionComponent2D for physical behavior and collision response. A RespawnComponent for giving Bounty the ability to get respawned after death. Last but not least there is a LifetimeComponent that will bind the existents of the entity on a certain amount of time. The TransformComponent is automatically attached to any entity that is derived from GameObject<T>. That’s it. We’ve just added a new entity to the game.

Now you probably want to see how to make use of all this components. Let me give you two examples. First the RigidbodyComponent. This component contains information about some physical traits, e.g. friction, density or linear damping. Furthermore it functions as an adapter class which is used to in-cooperate the box2d physics into the game. The RigidbodyComponent is rather important as it is used to synchronize the physics simulated body’s transform (owned by box2d) and the the entities TransformComponent (owned by the game). The PhysicsSystem is responsable for this synchronization process.

// PhysicsEngine.h

class PhysicsSystem : public ECS::System<PhysicsSystem>, public b2ContactListener

{

public:

PhysicsSystem();

virtual ~PhysicsSystem();

virtual void PreUpdate(float dt) override;

virtual void Update(float dt) override;

virtual void PostUpdate(float dt) override;

// Hook-in callbacks provided by box2d physics to inform about collisions

virtual void BeginContact(b2Contact* contact) override;

virtual void EndContact(b2Contact* contact) override;

}; // class PhysicsSystem

// PhysicsEngine.cpp

void PhysicsSystem::PreUpdate(float dt)

{

// Sync physics rigidbody transformation and TransformComponent

for (auto RB = ECS::ECS_Engine->GetComponentManager()->begin<RigidbodyComponent>(); RB != ECS::ECS_Engine->GetComponentManager()->end<RigidbodyComponent>(); ++RB)

{

if ((RB->m_Box2DBody->IsAwake() == true) && (RB->m_Box2DBody->IsActive() == true))

{

TransformComponent* TFC = ECS::ECS_Engine->GetComponentManager()->GetComponent<TransformComponent>(RB->GetOwner());

const b2Vec2& pos = RB->m_Box2DBody->GetPosition();

const float rot = RB->m_Box2DBody->GetAngle();

TFC->SetTransform(glm::translate(glm::mat4(1.0f), Position(pos.x, pos.y, 0.0f)) * glm::yawPitchRoll(0.0f, 0.0f, rot) * glm::scale(TFC->AsTransform()->GetScale()));

}

}

}

// other implementations ... From the implementation above you may have noticed the three different update functions. When systems get updated, first all PreUpdate methods of all systems are called, then Update and last the PostUpdate methods. Since the PhysicsSystem is called before any other TransformComponent concerned system, the code above ensures a synchronized transform. Here you can also see the ComponentIterator in action. Rather than asking every entity in the world, if it has a RigidbodyComponent, we ask the ComponentManager to give us a ComponentIterator for type RigidbodyComponent. Having the RigidbodyComponent we easily can retrieve the entity’s id and ask the ComponentManager once more to give us the TransformComponent for that id as well, too easy.

Let’s check out that second example I’ve promised. The RespawnComponent is used for entities which are intended to be respawned after they died. This component provides five properties which can be used to configure the entity’s respawn behavior. You can decide to automatically respawn an entity when it dies, how much time must pass until it get’s respawned and a spawn location and orientation. The actual respawn logic is implemented in the RespawnSystem.

// RespawnSystem.h

class RespawnSystem : public ECS::System<RespawnSystem>, protected ECS::Event::IEventListener

{

private:

// ... other stuff

Spawns m_Spawns;

RespawnQueue m_RespawnQueue;

// Event callbacks

void OnGameObjectKilled(const GameObjectKilled* event);

public:

RespawnSystem();

virtual ~RespawnSystem();

virtual void Update(float dt) override;

// more ...

}; // class RespawnSystem

// RespawnSystem.cpp

// note: the following is only pseudo code!

voidRespawnSystem::OnGameObjectKilled(const GameObjectKilled * event)

{

// check if entity has respawn ability

RespawnComponent* entityRespawnComponent = ECS::ECS_Engine->GetComponentManager()->GetComponent<RespawnComponent>(event->m_EntityID);

if(entityRespawnComponent == nullptr || (entityRespawnComponent->IsActive() == false) || (entityRespawnComponent->m_AutoRespawn == false))

return;

AddToRespawnQeueue(event->m_EntityID, entityRespawnComponent);

}

void RespawnSystem::Update(float dt)

{

foreach(spawnable in this->m_RespawnQueue)

{

spawnable.m_RemainingDeathTime -= dt;

if(spawnable.m_RemainingDeathTime <= 0.0f)

{

DoSpawn(spawnable);

RemoveFromSpawnQueue(spawnable);

}

}

}

The code above is not complete, but grasps the important lines of code. The RespawnSystem is holding and updating a queue of EntityId’s along with their RespawnComponent’s. New entries are enqueued when the systems receives a GameObjectKilled event. The system will check if the killed entity has the respawn ability, that is, if there is a RespawnComponent attached. If true, then the entity get’s enqueued for respawning, else it is ignored. In the RespawnSystem’s update method, which is called each frame, the system will decrease the initial respawn-time of the queued entitys’ RespawnComponents‘ (not sure if I got the single quotes right here?). If a respawn-time drops below zero, the entity will be respawned and removed from the respawn queue.

I know this was a quick tour, but I hope I could give you a rough idea how things work in the ECS world. Before ending this post I want to share some more of my own experiences with you. Working with my ECS was much a pleasure. It is so surprisingly easy to add new stuff to the game even third-party libraries. I simply added new components and systems, which would link the new feature into my game. I never got the feeling being at a dead end. Having the entire game logic split up into multiple systems is intuitive and comes for free using an ECS. The code looks much cleaner and becomes more maintainable as all this pointer-spaghetti-dependency-confusion is gone. Event sourcing is very powerful and helpful for inter system/entity/… communication, but it is also a double bleeding edge and can cause you some trouble eventually. I am speaking of event raise conditions. If you have ever worked with Unity’s or Unreal Engine’s editor you will be glad to have them. Such editors definitely boost your productivity as your are able to create new ECS objects in much less time than hacking all these line of code by hand. But once you have setup a rich foundation of entity, component, system and event objects it is almost child’s play to plug them together and build something cool out of them. I guess I could go on and talk a while longer about how cool ECS’s are, but I will stop here.

Thanks for swinging by and making it this far ![]()

Cheers,

Tobs.

In part one you didnt go into detail about System implementation. Would love a bit more detailed talk about your System<T> class. Great read as always cheers.